Moving a Book to the Marketplace

Getting Started: The Book

Before you can publish anything, you need to have something to publish. Simple enough, right? What’s important here is the quality of your work. Competition is fierce in the writing world; The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) estimates that well over two million new books are being published every year. If you want to stand out, that means you need the best manuscript possible and it means sending it to the people who want to read your type of book.

When you’re trying to reach greatness, I’ve found that only revision can get you there; lots and lots of revision. Read it out loud, let other people read it, take feedback and use it. These are all tools to perfecting your manuscript. Whole books are written about this, but I’m going to assume you’ve already done it. You’re holding a shiny finished manuscript, and it looks great.

Now you just need help with how to submit your book and have it end up on the shelves. That’s what I’m here for (hold the applause until the end, please). For the rest of this post, we’ll be looking at what kind of publication is right for you and how you can get started with it. There are lots of different types of publications, so we’ll start by breaking those down.

Literary Journals

Strictly speaking, these journals won’t get your book on any shelves. They’re an avenue to getting your name recognized, though. In fact, some publishers (for instance Press 53) don’t take submissions, but rather seek out authors based on previous publication and notoriety from contests and journals.

Literary journals are also the way to go if you have individual poems, short stories or creative nonfiction essays you want to publish. You may not have a whole book worth of material but can still get some of it out there and in circulation.

There are drawbacks to everything, of course. Many journals may offer trivial pay (some only pay with copies of the issue the author appears in) and will reserve certain rights over the author’s work that may leave you unable to publish that story or poem or what have you elsewhere. Medium.com has a great list of pros and cons worth considering.

Self-Publishing

This is truly the easiest way to publish, as it costs next to nothing (or in some cases nothing at all) and you can have a book in your hands in no time. Furthermore, it’s a much more viable form of publication than it ever has been. You’ve got complete creative control over the inside and the outside of the book and you alone get to say how it’s marketed and sold.

Sound too good to be true? Well, it’s not exactly, but it’s also not as simple as it sounds. If all you want is a book to look at or give to friends, yes, it’s that simple; NaNoWriMo used to run a deal with Amazon’s imprint CreateSpace giving free copies of winning books to anybody who finished a novel in November. I got a few nice-looking self-published books this way and shared them with my family, but that was the end of it. The books didn’t hit bookstores and I didn’t make a dime.

There must be some reason more than a million books were self-published in 2018 (according to Sarah Miniaci in a 2019 podcast). Well, if you’re able to do all the work of editors, publicists and market plans, and everything else a publisher might handle, she says this might be the right route for you. Also, while self-publishing is at its root very low cost, authors should be aware that all the work it takes to get your self-published novel seen is quite the opposite and can be financially taxing.

Historically, self-publishing has been hard in part because getting media attention for a self-published work has been all but impossible. Miniaci says that this is softening now but warns that certain genres (she points out literary fiction in particular) still don’t have much sway in the media without the backing of a publisher and that team of professionals to endorse it.

Hybrid Publishing

Hybrid publishing is the newcomer to the game and falls (as the name implies) somewhere between self and traditional publishing. In this model, you maintain creative freedom, but essentially hire a group of literary professionals to help you through the process of editing, publication, marketing and sales. It’s like self-publishing with help. It’s like traditional publishing with a price tag.

Nailing down a definition of this model is hard. Jane Friedman says, “Hybrid publishers combine aspects of traditional publishing and self-publishing. Beyond that, however, it is challenging to define what such companies have in common.” Why is that? It’s because hybrid publishers work in a number of different ways to make money and make successful books. Writer’s Digest has narrowed down four in an article that might be enlightening if this is a route you’re considering.

Ultimately, whichever form of hybrid publishing you settle on, you can expect some things to be the same. First, expect to assume all the overhead costs. Remember that you’re paying them to publish and promote your book; any money you make back will be in royalties as the book sells. In many cases, this will not balance the initial investment.

Next, remember that this team is working for you. In a traditional setup, the publishing team works for your book, doing everything they can to make sales. With hybrid publishing, you remain as something of a project manager, and retain full creative control over your work. This gives you the freedom to put out exactly the vision you had in mind, but also allows a huge risk as the decisions all fall squarely on you.

Traditional Publishing

Traditional publishing is still seen as something of the holy grail. There are some solid reasons for this, but know that all publishers aren’t created equally. Still, let’s look at what makes this so appealing. One thing is the financial incentive; according to The Authors Guild, “self-published authors as a whole still earned 58% less than traditionally published authors in 2017.” In case anybody was unsure, that’s a huge gap.

Another reason, also financial, is that writers don’t have to pay anything (except maybe a reading fee) to be traditionally published. In this model, the publisher takes the full financial burden of the book, hoping to recoup losses on sales. Of course, it’s worth noting that this rarely happens. As one Quora user said, “Out of 10 books, 2 were "successful" - meaning they returned in gross profit what you had invested in them. One in ten was a hit, meaning that you actually made some money at it, and covered the vast majority (but maybe not all) of your losers.”

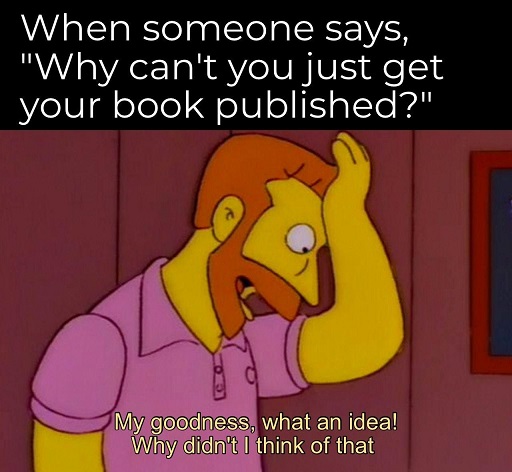

What that means to authors is that traditional publishers have every reason to accept only the absolute best manuscripts to come their way. Part of how many publishers screen submissions is by limiting them to only solicited manuscripts, meaning ones being sent by a writer’s agent. This blockage can stop new writers from even getting their foot in the door, but all is not lost!

As it stands, the Big 5 currently dominate the traditional publishing world. They’re the major players in which books make it to shelves and in the media, but they’re not the only way to get a book traditionally published.

Small Presses

With the onset of digital technology allowing small presses to print on demand, these little guys are actually more viable than ever. In fact, given the way major publishers are putting out books with the sole aim of making money, small presses are completely necessary to keep new voices alive and healthy. The Atlantic has a great article about this, but it’s enough for me to say that small presses are important for publishing work other powerhouse publishers won’t or can’t.

The downside here is that they obviously can’t make as much money as the moneymakers, right? While this is true, if your goal is to hit the best-seller list with a Big 5 publisher, having prior published work can at least help you get noticed. Like literary journals, these can be considered as an opportunity to build your voice, your name, and your platform (more on that to come). Small presses are doubly helpful for this, as they tend to work more closely with the author on layout and design, among other aspects of the process.

There are literally hundreds of small presses to choose from. When you’re selecting, keep in mind that each has its own aesthetic and may not be suitable to the book you’re looking to release. If it sounds like a lot, it is; we’re lucky there are folks like those over at EntropyMag.org who put together this small press database.

The Innerworkings of Sales

Those are basically the ways you’re going to sell your book, but there’s a lot that goes on after that. Before it actually hits the market, your book will be pitched and sold time and again by sales reps at conferences, meetings, book fairs, and other publisher events. I can’t begin to cover them all in a single sub-header, but it’s important to give you the basics.

At sales conferences, a few professionals including editors, marketing and publicity specialists pitch, not just the plot of your book, but every detail from visual aesthetics to possible marketing issues. Each book is discussed thoroughly, down to every detail that could impact sales. This is especially important to be aware of for self-published authors, who will need a distributor to help move sales forward in this arena. Jon Mayes does a great job of describing the sales conference in this post on his own blog.

Another avenue for getting your book noticed and sold is a book fair. The Frankfurt Book Fair is the largest in the world and has been running for five centuries. Here in the states, we have to settle for the massive (but somewhat less massive) BookExpo America. Professionals from all related areas, from librarians to book buyers, flock to these, and they remain a valid way to be seen.

Your Platform

As you're pushing your work towards ever increasing greatness, one thing you’re going to need is a platform to stand on. This is your aesthetic as a professional, but also your cohort and your social presence. For some people, this means being great at social media, but in the podcast I mentioned up above, Sarah Miniaci tells us it doesn’t have to mean that and that sometimes it shouldn’t.

Personally, I’m not great at keeping up with my social media. I can relate. What I (read: we) have to do is keep working. A writer has to always be working, either at the craft or at their presentation of it. As the author, you are what presents first about your craft, and how you display and conduct yourself defines how your work is received. Keep that blog going. Review a novel or a story. Contribute to literary journals. You want to keep your name out there in the best light that you can.

Equally important to your platform is your cohort; as you work, you’ll encounter editors and peers and other professionals in the field. If you can bring them into your cohort, help them and work with them, they’ll be more likely to do the same for you. Having a strong foundation of people around you will help with literally everything you try to do, even if the help is only moral support.

TL;DR (That’s Okay, I Forgive You)

There are lots of ways to go about publishing your book. No matter which route you take, you need a good manuscript and a good platform to appeal to buyers. Once you have that, decide between self-publishing, hybrid or traditional. They all have benefits and drawbacks, but the short form is self-publish if you’re willing to put in the work, hybrid if you’re willing to pay somebody else to, or traditional if you enjoy being scrutinized prior to publication (I jest – don’t forget that traditional publication is the most profitable!).

Once you’ve made a book or that manuscript is accepted by a publisher, you’ll enter the realm of sales. This is a fierce battleground where your book will be measured against the marketability of every other book being released. Good luck.

Finally, just remember to keep writing. That’s what makes you a writer, not market sales. That’s what will build your brand and your platform. The writing doesn’t bring success, it is success.

REFERENCES:

- "UNESCO | Building Peace in the Minds of Men and Women" https://en.unesco.org/ Accessed 4/17/21

- "Press 53" https://www.press53.com/ Accessed 4/17/21

- "The Pros and Cons of Submitting to Literary Magazines | By Mary K Gowdy" https://medium.com/@marykatherinegowdy/the-pros-and-cons-of-submitting-to-literary-magazines-e3f829a0a441 Accessed 4/17/21

- "NaNoWriMo" https://nanowrimo.org/ Accessed 4/17/21

- "https://www.createspace.com/" https://www.createspace.com/ Accessed 4/17/21

- "A Discussion on Publishing Options - Podcast - Smith Publicity" https://www.smithpublicity.com/2019/12/new-podcast-episode-a-discussion-of-publishing-options/ Accessed 4/17/21

- "What is a Hybrid Publisher? | Jane Friedman" https://www.janefriedman.com/what-is-a-hybrid-publisher/ Accessed 4/17/21

- "What is Hybrid Publishing? Here are 4 things you should know" https://www.writersdigest.com/self-publishing-by-writing-goal/what-is-hybrid-publishing-here-are-4-things-you-should-know Accessed 4/17/21

- "Six Takeaways from the Authors Guild 2018 Author Income Survey" https://www.authorsguild.org/industry-advocacy/six-takeaways-from-the-authors-guild-2018-authors-income-survey/ Accessed 4/17/21

- "What Does a Traditional Book Publisher's Business Model Look Like?" https://www.quora.com/What-does-a-traditional-book-publishers-business-model-look-like Accessed 4/17/21

- "The Big 5 Trade Book Publishers in the U.S." https://www.thebalancecareers.com/the-big-five-trade-book-publishers-2800047 Accessed 4/17/21

- "Why American Publishing Needs Indie Presses" https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2016/07/why-american-publishing-needs-indie-presses/491618/ Accessed 4/17/21

- "Small Press Database - ENTROPY" https://entropymag.org/small-press-database/ Accessed 4/17/21

- "A Tale of Two Publisher's Sales Conferences, Part One" https://advancereadingcopy-jon.blogspot.com/2013/04/a-tale-of-two-publishers-sales.html Accessed 4/17/21

- "Frankfurter Buchmesse" https://www.buchmesse.de/en Accessed 4/17/21

- "BookCon" https://www.bookexpoamerica.com/ Accessed 4/17/21

April 17, 2021

Ben SD lives in Ohio with his wife, cat, dog, and a whole bunch of kids. He's been all over the world but wants to see so much more of it. He's a writer because something in his brain says he has to be. At the time of this post, Ben is working on his Master's degree for Professional Creative Writing with a focus on Fiction. This keeps him busy, but he's always working on some kind of new material at the same time.